Ulay | Polaroids at Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam (2016)

Thanks to the digital camera and the Internet, instant photography has become an integral part of our daily lives. Before the digital age, however, it was the Polaroid Company that made the instant photography experience accessible to the average person with its launching of the first fully automatic instant Polaroid camera in 1972 – a product that became extremely popular virtually overnight. The exhibition Ulay | Polaroids, organized by the Nederlands Fotomuseum (Netherlands Photo Museum) in Rotterdam, proves that the artistic possibilities of Polaroid photography extend beyond taking amateurish post-Instagram snapshots. According to the museum, it is the first-ever exhibition dedicated solely to polaroids by the versatile artist Ulay. From the 1970s on, Ulay pioneered the use of the Polaroid as an artistic medium and has since been building an extensive oeuvre. The exhibition is a joint project of the Nederlands Fotomuseum and the Rabo Art Collection, which owns a number of significant Ulay Polaroids, and is accompanied by a catalogue.

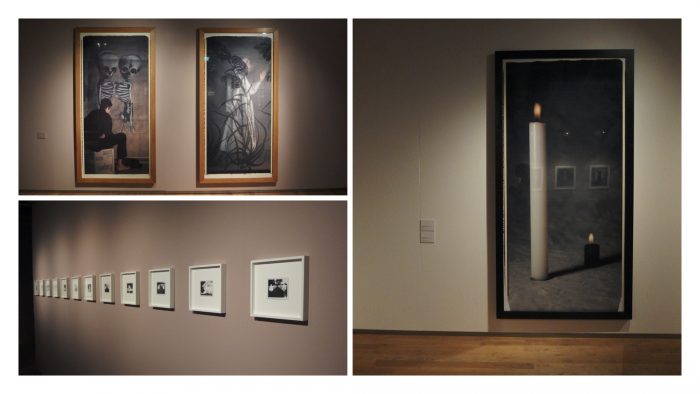

Exhibition view. Photo © Malika M’rani Alaoui

Ulay, pseudonym of Frank Uwe Laysiepen (Solingen, Germany, 1943), is probably best known for his performances of the late 1970s and 1980s with his then lover Marina Abramović. Prior to creating this performance art, however, he had previously worked with the Polaroid camera and taken thousands of instant photographs of himself. In these images, Ulay explored his own personal identity as well as the limits of the human body and soul. These are powerful Polaroids, often manipulated with text either typed-out or cut up into collages. Ulay’s Polaroids are very straightforward. Lighting conditions or aspects of form were of no interest to him: his aim was to capture reality. In his use of the Polaroid image, Ulay was extremely innovative, often undertaking unusual experiments. A well-known example are his ‘Polagrams’: life-size Polaroids which he created by stepping into a ‘camera’ consisting of two connecting rooms, with a hole and a large lens built into the wall separating them.

Ulay was born in a bomb shelter in Solingen, Germany, during the Second World War. He grew up as an only child; by the age of fifteen, he had lost both his parents. After being trained as technical photographer, Ulay established a photography business specialised in industrial and architectural photography. In 1969, however, he decided it was time to make a new start. Ulay left everything behind him and subsequently moved to Amsterdam, where he was first introduced to Polaroid photography. The city just happened to be the location of the Polaroid Company’s European headquarters. From the beginning, Ulay was fascinated by the Polaroid medium, the particular aesthetic of the image, and its instant quality. In Amsterdam, he came into contact with Manfred Heiting, former art director at Polaroid International. In light of his technical background, Ulay was asked to work as a consultant for Polaroid. In exchange, he was granted unlimited access to Polaroid films and equipment. This enabled him to experiment on a large scale and to begin using the Polaroid camera to document a personal search for his own identity in relation to social conventions.

The quest for identity

Most artists develop a signature style over the years to which they adhere. Ulay, however, never ceased with experimentation and continuously reinvented himself. In a career by now spanning more than four decades, the artist has built a highly heterogeneous oeuvre that defies any traditional classification – even Ulay himself asserts he is not the typical ‘signature artist’. Ulay’s oeuvre is nevertheless clearly recognizable based on the investigation of identity, a common thread in his oeuvre. His existential quest is reflected in all of his images, giving his work a sense of vulnerability and displaying an aesthetic extending beyond mere aspects of form. The exhibition in the Nederlands Fotomuseum does not provide an exact overview of Ulay’s stylistic development over the last forty years, but focuses on the never-ending investigation of the artist’s identity. As such, the viewer becomes an observer of his intimate search. At the same time, the show highlights the endless applications of instant photography made possible by Polaroid, an innovative company that almost sank into oblivion, due to the fact that instant photography had become so common.

Ulay | Polaroids features both Ulay’s early and most recent work, dispersed across two spaces in the museum’s basement. The first thing you see upon entering the exhibition is a documentary about the artist, filmed in part during preparations for the exhibition and including an interview. This is a brief and easy way to become acquainted with Ulay, without having to read too much in advance. As the information stated on the museum labels is very basic, watching the introduction film is highly recommended. In this first room, the entire space appears as an intended introduction to Ulay, highly personalized with the exhibiting of some of his favorite Polaroid cameras as well as drawings from his sketchbook. While offering the visitor added contextual information with respect to the artist, this kind of presentation is more or less an attempt to bridge the gap between art and the general public – an approach that seems to be very popular in the museum world nowadays.

Exhibition view. Photo © Malika M’rani Alaoui

The second space is reserved for Ulay’s Polaroids. The works are arranged into series that show the different phases of the artist’s self-investigation. Upon entering the space, the first work that draws one’s attention is a more-than-life-size Polaroid, one of the largest ever taken (Self Portrait, 1990, 288 x 122 cm). This ‘Polagram’, according to Ulay, is the key piece of the exhibition. To produce this Polaroid, Ulay stepped inside the camera to draw a vase on the negative by using miniature lamps attached to his hand, which itself produced a shadow as well recorded at the same time. As a result, you see the white contours of a vase against a dark background, with the shadow of a hand coming out in the middle, as if it is trying to touch you. Due to this special technique, Ulay was able to combine performance art with photography, thus literally becoming one with the artwork. In his works, Ulay uses the body as a starting point for interrogating the meaning of the human condition and investigates how bodily experience can be translated into an artistic unity. Performance art is the best medium to explore this; the process of the act forces you to come closer to yourself. Ulay made this work two years after his break-up with Abramović, at a time when his interest shifted to the dematerialization of the body. He sees the vase as the vessel of the spirit and uses it metaphorically, i.e. as a substitute for the body – a traditional concept, both in the West and the East.

The quest for one’s identity is something that everyone deals with at certain points in their life. Our identity, in the eyes of others, can be regarded not just as who we are, but also as what we offer to society. The malleability of identity is a common theme in Ulay’s early work. During the period 1970-1975, he produced numerous ‘Auto-Polaroids’, as he called them. For these ‘Auto-Polaroids’, Ulay carried out a variety of actions dressed up as different characters, which he recorded with the Polaroid. The camera functions here as a mirror, which forces him to examine himself more thoroughly and to investigate his own identity. In S’he (1972-1975), for example, Ulay played with the notion of a ‘half-man, half woman’ by photographing himself dressed partly as a man and partly as a woman. A photographic identity is changeable in countless ways, but photography is limited to the surface: Ulay wished to delve deeper into the psychology of identity. At this point, he started with performances involving self-mutilation, as a manner of self-investigation. He cut himself, or had himself tattooed, and documented this with the Polaroid camera. By doing so, Ulay was trying to get literally and figuratively under his own skin, coming closer to his suspected identity. For example, a series of black-and-white Polaroids entitled Soliloquy (1974) shows the naked artist sitting in a bathroom as he cuts his fingers with a knife, subsequently wiping off his bloody hands on the white wall.

With respect to Ulay’s recent work, the Nederlands Fotomuseum presents five of his latest instant photographs, taken at the request of the Rabo Art Collection. The series Joy (2015) consists of one hundred self-portraits. We see a tan Ulay – looking older, but healthy – floating in a swimming pool surrounded by rose petals. In this work, the artist highlights the importance of water in sustaining life on earth. The character of this Polaroid series is optimistic, or as its title suggests, joyful. After more than four decades, Ulay declares he has relinquished his quest for identity. It is this acceptance that is perhaps reflected in his latest work. In any event, Ulay’s quest has resulted in an interesting oeuvre that is definitely worth seeing.

Exhibition view. Photo © Malika M’rani Alaoui