Every Sunday a new artist and artwork

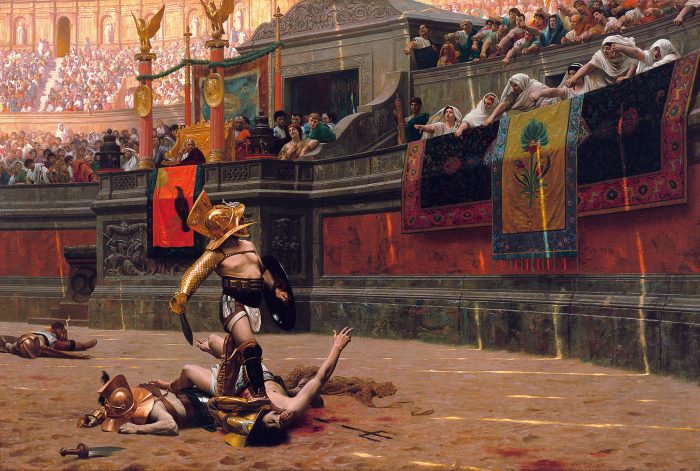

Pollice Verso by Jean-Leon Gérôme

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904) was a French painter and sculptor in the style now known as academicism. The range of his oeuvre included historical painting, Greek mythology, Orientalism, portraits, and other subjects, bringing the academic painting tradition to an artistic climax.

A special theme within Gérôme’s oeuvre of history pieces are the arena scenes he made between 1859 and 1883. They can be counted among his most popular and spectacular paintings and were reproduced and distributed on a large scale. These reproductions were used in various ways – for example for book illustrations or magic lanterns – and the images Gérôme created of ancient Rome have contributed to our perception of life in classical antiquity.

One of Gérôme’s most famous arena scenes is Pollice Verso (1872). We see a gladiator in the Coliseum, his foot on his opponent’s chest. The face of the winning man is not visible through the helmet he is wearing, but his head is pointing upwards towards the audience. The gladiator on the ground raises his arm, begging the audience for mercy. But the people in the spectators keep their thumbs down – pollice verso in Latin – as a sign that they don’t want to spare him. Along with gladiators, Vestals, and spectators, the picture shows the emperor in his box. Like many historical or ethnographic paintings of the era, Pollice Verso piqued the prurient interest and indulged the voyeurism of viewers while allowing them to feel a sense of moral superiority over another (previous, non-Christian) culture.

At first glance, Pollice Verso seems organized around a single, powerful moment, in line with the conventions of the French tradition of history painting. For this art it was considered important that the painting conveyed (pictorial) unity and that the representation should be recognizable at a glance. However, Gérôme played with this and did not followed the conventions too strict. For example, the visual field of the representation extends beyond the boundaries of the painting. Figures are cut off and positioned off center, which gives the suggestion that the narrative continues beyond the painting’s frame. When we take a closer look at the spectators, it is noticeable that they are not all focused on that one action moment and we may wonder what else to see. There seem to be different, ephemeral stories taking place within this scene, which makes it difficult to focus. This is reinforced by the panoramic format (96.5 × 149.2 cm) of the painting, which makes our eyes keep looking from left to right. In this way the whole scene unfolds as a sequence of moments, so that the painting is no longer static, but a suggestion of movement is made.

Jean-Leon Gérôme, Pollice Verso, 1872. Oil on canvas, 96.5 × 149.2 cm. Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

The Beach near Trouville by Eugène Boudin

The French painter Eugène-Louis Boudin (1824-1898) was born in Honfleur as the son of a ship’s captain. As a young boy, he worked on a steamboat that ran between Le Havre and Honfleur. But after he fell overboard and almost drown, his mother decided to send him to school. In 1835 his father abandoned seafaring and opened a store for stationery and frames in La Havre. Having opened up his own frame shop, the young Boudin came in contact with the artists Jean-François Millet and Jean-Baptist Isabey, who encouraged his early artistic pursuits. At the age of 22, Boudin shuttered his shop and started painting full-time.

The majority of Boudin’s works are small landscapes of the harbors and beaches of the coast of northern France, informed by a keen eye for social detail. Up to the 19th century, the beach was a place where fishermen used to go to work and not a place to spend your spare time. However, from the mid-1800s, European elites began touting the curative qualities of fresh air, exercise and sea bathing. The Normandy coast became particular popular among the French upper classes who wanted to escape Paris, and the artists followed, to paint their portraits, do seascapes and make some money under the sunny-cloudy Norman skies.

The Beach near Trouville (c. 1865) is one of Boudin’s many paintings that he made in Trouville, – a popular resort for Parisians escaping the summer heat. We see a group of fancily dressed men and women (long skirts, flowery hats, bowlers, suits, vests) sitting and strolling on the sand, holding parasols against the sun. Instead of trying to individualize the silhouettes, the artist, in a panoramic vision, captures the crowd of the seaside, which forms a frieze occupying the median space of the coastline, between beach and sky. The absence of precise contours of the characters, their way of blending into the site, contribute to evoking this social body as a whole. Boudin expresses here the very essence of modern life. The light treatment of the brushstroke, which matches the variations in light and the movement of the clouds, heralds the research of the impressionists.

Eugène Boudin, The Beach near Trouville, c. 1865. Oil on canvas, 35.7 x 57.7 cm. Artizon Museum, Tokyo.

The execution of the doge Marino Faliero by Eugène Delacroix

In his paintings, the Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix (1798 – 1863) aimed to capture all the moments and emotions from a story that interested in one scene. A good example of this is The execution of the doge Marino Faliero (1826). The painting is a free interpretation of Byron’s drama with the same title, which was staged in both London and Paris shortly after its publication in 1821. The story takes place in fourteenth-century Venice and is about Marino Faliero, the 53rd Doge of Venice. Faliero had already passed the age of seventy and was – it is said – slightly senile when he was elected. He despised the nobility, who, he thought, looked down on him, and attempted a coup d’etat in April 1355, aiming to take effective power from the ruling aristocrats. The coup failed and Faliero was sentenced to death together with ten accomplices, after which his body was hanged at the Doge’s Palace.

In The execution of the doge Marino, Delacroix broke with existing conventions. Most of all, the composition is not centered around a limited number of people who performing related actions. Within this work there are several stories, which makes it difficult to name at once which scene is depicted here. In fact, Delacroix recorded three different moments: the past (the execution), the present (the raising of the sword) and the future (the citizens who want to enter the palace). By capturing several moments in a painting, Delacroix suggests a passage of time and gives the painting vitality. Moreover, with this work Delacroix broke an important rule for history pieces: Faliero has already died and the drama that is considered so suitable for history pieces is therefore missing. While in Byron’s play the execution is the highlight, Delacroix also deviates from his inspiration. Delacroix did not choose the most fertile moment but depicted the scene that follows.

Delacroix’s choice to depict only the heads of the incoming crowd is equivalent to directing a play and creates a certain tension by creating the illusion of action: as if the figures can move at any moment. By using an off-stage technique, Delacroix ensures that the performance does not stop within the frame. The emptiness in the middle – through the positioning of the white stairway – creates an enormous distance between the nobility and the ordinary bourgeoisie. Moreover, the emptiness makes the viewer’s eye look for a relationship between the different moments.

Eugène Delacroix, The Execution of the Doge Marino Faliero, 1826. Oil on canvas. Wallace Collection, London.

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Beautiful Roman ladies relaxing in marble decors, carelessly leaning against an azure blue background or looking out over a calm sea. The interiors of Roman churches, archaeological excavations in Pompeii and everyday, lifelike scenes from classical antiquity take you on a journey to the past.

The nineteenth-century Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema was born in 1836 in the province of Friesland in the north of the Netherlands. In 1852 the young Alma-Tadema went to Antwerp to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts there. The Antwerp Academy had a good reputation internationally and attracted a lot of foreign artists, many from the Netherlands. Tadema continued his studies in the studio of Louis De Taeye, who taught courses in history and historical costume at the Antwerp Academy. De Taeye introduced him to history books about the Merovingian period – which would become a lifelong fascination of the artist – and encouraged him to pursue historical accuracy in his paintings.

In 1863 Tadema visited Naples and Pompeii, where he witnessed the excavations in Pompeii. This developed his interest in depicting the life of ancient Greece and Rome, especially the latter since he found new inspiration in the ruins of Pompeii, which fascinated him and would inspire much of his work in the coming decades. He also collected antique objects himself and in this way reconstructed the past in his studio – and on his canvases. With his brush he was one of the firsts academic painter to really bring a lost world to life.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888. Oil on canvas, 132.1 x 213.9 cm. Collection Juan Antonio Pérez Simón, Mexico.

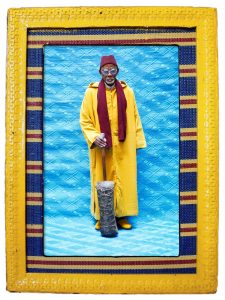

Abdul Qadir Oktaoa by Hassan Hajjaj

This rainy Sunday needs some colorful post-pop art. Made by Hassan Hajjaj, a Moroccan-born artist, who is heavily influenced by London’s club, hip hop and reggae culture as well as by his North African heritage. Sounds as cool as it looks. Hajjaj is a self-taught and incredibly versatile: from performance art, photography, installations and interior design to fashion and furniture design … In short, an artist to wacht out for!

Abdul Qadir Oktaoa, photography by Hassan Hajjaj 2015/1436. Ed. of 5. Courtesy of the Artist